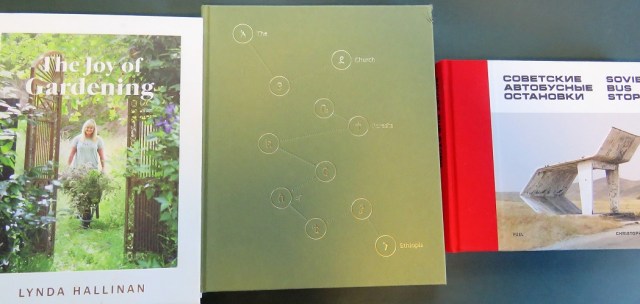

Almost to the day, it is two years since we first went into lockdown in this country, when we realised – well, most of us realised – that Covid was real and like nothing we had dealt with before. Life changed for most of us. Lynda Hallinan’s book ‘The Joy of Gardening’, came out late last year but appears to have its genesis in the earlier lockdown days. It is a book firmly anchored in our Covid present.

I have written before of myself that ‘I garden so I have a lot of thinking time’. The same is true of Lynda. Most of us know her as an irrepressible, bright, bubbly person who is genuinely keen on gardening and plants. This book is more intimate, more reflective at this time when our focus is closer in, more defined by our immediate environment as we try to make sense of a world that has changed.

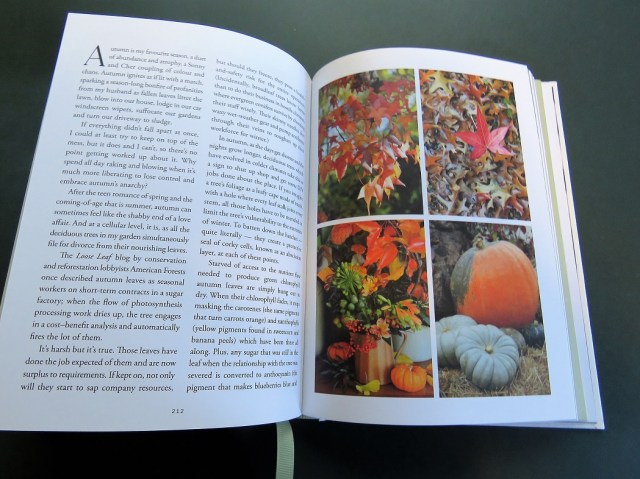

There is a soft focus to this book, quite a bit of nostalgia and thoughts about what gardens and plants mean at a personal level, leavened by the author’s irreverent humour. There are lots of of romantic, soft-focus photos by Sally Tagg but we know these are just mood-setters because all the photo captions are banished to the last two pages of the book and then just recorded as plant names. That is a case of a book designer thinking that the look is more important than reader convenience. That aside, it is a beautiful hardback and I do love me a book with a built-in book marking ribbon.

Lynda is a journalist and it shows. She has an immensely readable style and the words flow with confidence. While divided into ten sections (Making Memories and Love & Loss are two), each section has a number of separate pieces loosely related to the theme. It means you can pick up the book and read a page or two and it stands on its own. I have been known to refer to this as loo reading but you may prefer to think of it as coffee-break reading. It can detract from a sustained reading session because those short bits are so short and snappy but there is a surprising amount of good information included. I think it is a charming book, best savoured in smaller bites and particularly relevant at this time.

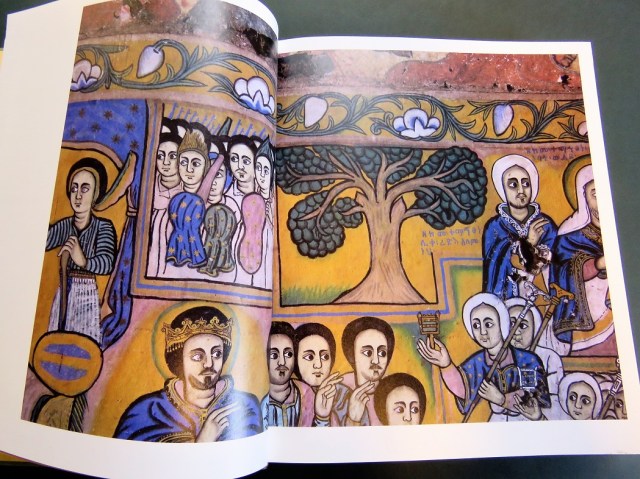

I know very little about Ethiopia which only seems to reach our news when there is famine or civil war. It did of course give us Haile Selassie with the odd spin off of the Rastafarians but well before that, it was an ancient civilisation where humans were first recorded in modern form and an early Christian nation. It is also one of the fastest expanding economies in the world today, with a predominantly rural population. This has led to major deforestation which is the subject of a book by Kieran Dodds titled ‘The Church Forests of Ethiopia’.

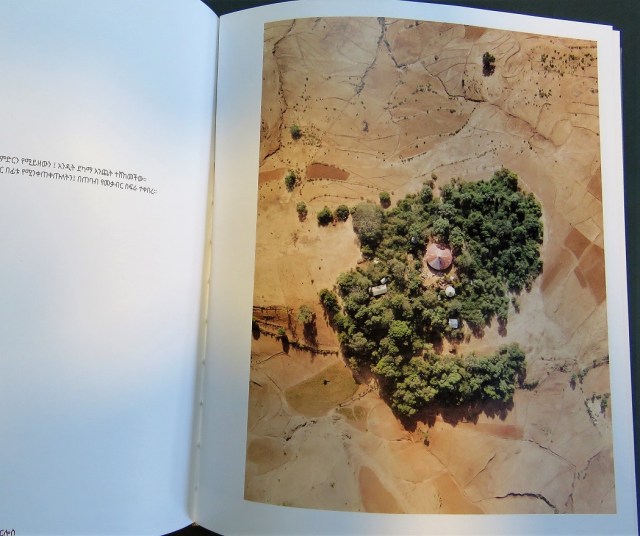

It is predominantly a book of photographs of the local people and the environment in Amhara Province with a lot of aerial shots showing the agricultural deserts where the only remaining native forests are patches of green surrounding churches. The Tewahedo Orthodox Christian churches are a distinctive round shape like domes or saucers and the reason why the small patches of remnant forest around them survive is because they are sacred. Think miniature gardens of Eden in a desert. It is a unique landscape.

The book is a fundraiser to support the organisations and groups involved with replanting to extend the existing forests and particularly creating links between the forested areas which enables native animal and insect life to move from one area to another. You will be supporting critical environmental work if you buy this book but also, you may enjoy having this rather gentle pilgrimage through the church forests of Ethiopia in your bookcase. The one thing it lacks is any information on what the dominant native plant species are but I guess if you want to know more, you could Google ‘woody flora of dry Afromontane areas in Ethiopia’.

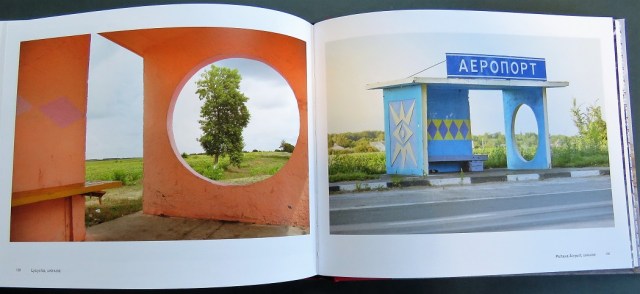

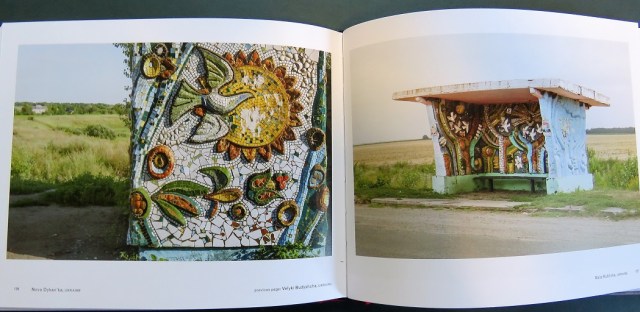

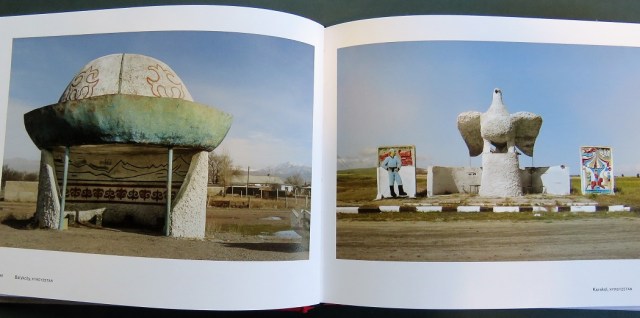

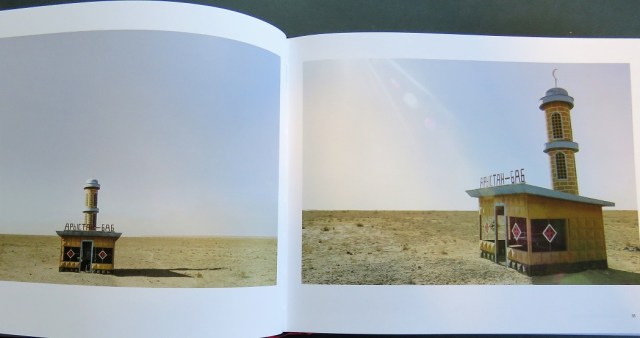

Nothing whatever to do with gardening, but a book I felt belonged in my bookcase in a totally random manner is ‘Soviet Bus Stops’ by Christopher Herwig. It is what it says – a collection of photographs of bus shelters throughout the former Soviet Union. These shelters date back to a time when private cars were a luxury, when the dreary conformity of the Brezhnev years spanned the era from the 1960s through to the start of the 1980s. This is apparently known as the time of stagnation and these bus shelters are a memorial to the triumph of individual creativity and flamboyance in a repressive regime.

Architects, artists and designers could unleash themselves – within a budget – and unleash themselves they did with marked regional differences and varying materials. I feel I owe it to Ukraine to show their shelters which are charming but not of the same level of flamboyance and scale as some other areas – favouring form over function as one of the brief introductory essays says. There aren’t just a few of these bus shelters, there are many although I am not sure yet whether I feel the need to buy the second volume of this odd phenomenon.

It is a quirky little book but also a record of the triumph of human spirit, even more so in the context of what is happening in that part of the world right now.

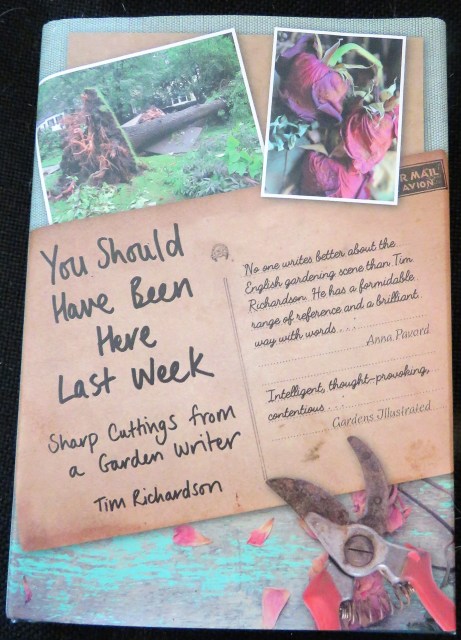

A sign of an interesting book is when you find yourself keeping it to hand so that you can refer to it in numerous conversations. Not a showy book, in this case. There is a not a photograph in sight and the production values are what might be called utility, so it fails to fit the traditional definition of a coffee table book. Perhaps the descriptor of ‘aircraft reading’, or even ‘loo reading’ captures the format – short pieces between about 700 and 1200 words long which can be read in a few minutes. But for the last few weeks it has been sitting close to hand as we discuss many of the points made in its text.

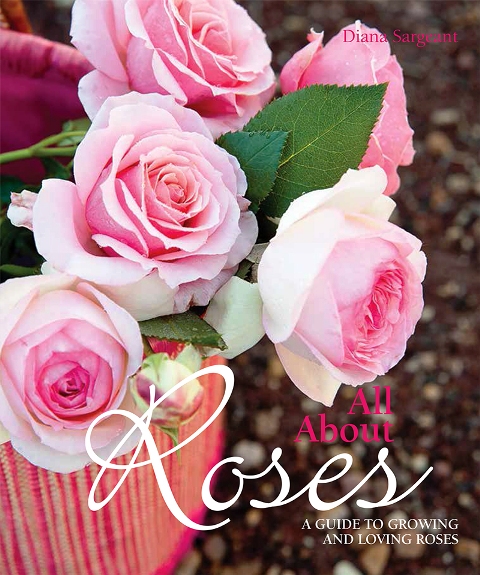

A sign of an interesting book is when you find yourself keeping it to hand so that you can refer to it in numerous conversations. Not a showy book, in this case. There is a not a photograph in sight and the production values are what might be called utility, so it fails to fit the traditional definition of a coffee table book. Perhaps the descriptor of ‘aircraft reading’, or even ‘loo reading’ captures the format – short pieces between about 700 and 1200 words long which can be read in a few minutes. But for the last few weeks it has been sitting close to hand as we discuss many of the points made in its text. I approached this book with a little trepidation because it seemed to be part of the trend to release Australian publications in this country, assuming that they will be equally relevant here with no significant difference in conditions and plant varieties. In this case it works. This is a charming and helpful book written by somebody who combines vast experience with a genuine love for the topic. The author ran a rose nursery for 25 years where they chose to go to organic production well before many others came to realise that our growing of roses had become bad practice environmentally. There is no doubt it would be easier in Australia to grow good roses without chemical intervention because of their dry climate, but her experience is invaluable. I am not sure how readily available some of her alternatives are in this country yet – but they are stocked even by Bunnings in Australia so if the demand is here, I am sure we will see them soon. That is eco-fungicide, eco-oil, eco-neem and eco-amingro.

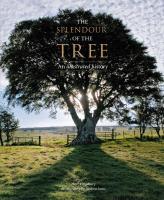

I approached this book with a little trepidation because it seemed to be part of the trend to release Australian publications in this country, assuming that they will be equally relevant here with no significant difference in conditions and plant varieties. In this case it works. This is a charming and helpful book written by somebody who combines vast experience with a genuine love for the topic. The author ran a rose nursery for 25 years where they chose to go to organic production well before many others came to realise that our growing of roses had become bad practice environmentally. There is no doubt it would be easier in Australia to grow good roses without chemical intervention because of their dry climate, but her experience is invaluable. I am not sure how readily available some of her alternatives are in this country yet – but they are stocked even by Bunnings in Australia so if the demand is here, I am sure we will see them soon. That is eco-fungicide, eco-oil, eco-neem and eco-amingro. Despite the subtitle, An Illustrated History, this handsome book is more for the coffee table than a library reference. The selection of trees – and there are about 100 different tree species, each given at least a double page spread, sometimes more – is a little too random and eclectic to make this useful as a reference book. It is more testimony to a love affair than a work of scholarship.

Despite the subtitle, An Illustrated History, this handsome book is more for the coffee table than a library reference. The selection of trees – and there are about 100 different tree species, each given at least a double page spread, sometimes more – is a little too random and eclectic to make this useful as a reference book. It is more testimony to a love affair than a work of scholarship.