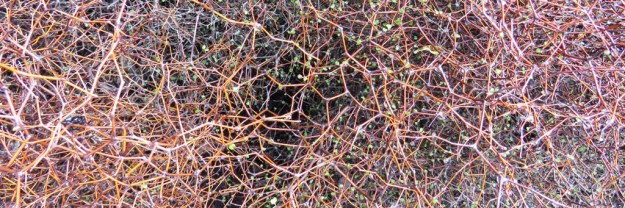

In reality, it is even more insignificant than in this photo

There are not many plants as disappointing as our white nepeta. Before you rush to set me right by telling me that your white nepeta is absolutely gorgeous, I will declare that I have had a look at the internet and I see there are various white forms around and most of them look to be an improvement on the one we had here. Note the past tense. We have taken it out – and there was a fair swag of it – and it is now on the compost heap.

Nepeta is not exactly a plant of class and distinction but it is easy to grow, forgiving and on its day, it gives a haze of colour as well as feeding the bees. We were quite taken by its use in plantings that resemble rail tracks in a couple of English gardens we visited, despite my reservations about both the use of edging plants and planting in rows.

The railway track effect at Tintinhull in England where the nepeta looked lovely

We came home and looked at our nepeta in askance. I could not remember ever being wowed by its lilac haze in bloom but it was certainly spreading widely. This season, I said to myself, I will take special notice. It was not growing in a spot I walk past every day but it was relatively prominent. Dammit, I thought, when I saw seed heads on it. How did I miss it again? Was it really such a flash in the pan? Mark, it turned out, had been thinking the same. We stood looking at it together and realised it was possibly the world’s most boring white nepeta with the tiniest of insignificant flowers at the same time as setting seed. Sure the bumble bees liked it but they will like our lilac nepetas just as much or maybe more. Mark has a tray of seedlings raised, ready to plant as an immediate replacement.

Mark is unconvinced by the notion of white nepeta which, in his mind, contradicts the very nature of nepeta which should be blue or lilac. But the joke is on us that we had both failed to notice that ours never flowered in the right colour.