I said in last week’s post that I would return to Waltham Place and Knepp Castle, along with ‘rewilding’. Both are visited in episode 4 of Monty Don’s British Gardens series.

Waltham Place first because we were fortunate to talk our way into seeing it in person in 2014. It was certainly challenging and interesting and continues to be food for thought a decade later. I have written about it here, but without photographs because one condition of entry was that we not take photographs. Did we like it? Not particularly. We prefer prettier gardens with more focus on plant interest but that was irrelevant then and remains so now.

In retrospect, I think it may sit as a side adjunct to the whole genre of conceptual gardens. In a pure form, conceptual gardens are where design, space and integrated art installations – the last being of a symbolic, architectural, intellectual-bordering-on-esoteric nature – take precedence over more traditional garden values. Think Little Sparta or Plaz Metaxu To some extent, I think Belgian designers Jacques and Peter Wirtz belong here too. They are landscape architects and their speciality is treating outdoor space as architecture where form and space are the most important aspects. We have never sought these gardens out because our interests take us in other directions.

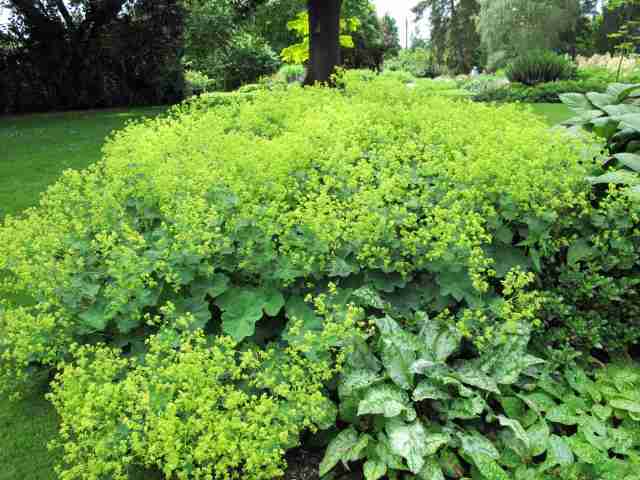

Why would I put Waltham Place into this wider genre? Because the concept and philosophy that underpins the garden is arguably more important than what you see. It seemed very much an intellectual exercise. Planted around 2000, it utilised all the existing elements of a traditional, English, Arts and Crafts garden (huge brick pergola, walled garden, gazebo on stilts, ponds, graceful manor house etc) but the plantings are on the wild side with a very light hand indeed on maintenance. The designer was Dutchman, Henk Gerritsen and it adheres closely to the philosophy of his muse from an earlier generation, Mien Ruys: “a wild planting in a strong design”. Dare I say it – the strong design element at Waltham Place means that it photographs and films rather better than the actual experience of visiting in person.

Gerritsen died at a relatively young age in 2007. Had he lived longer, I think it would have been interesting to see how his style evolved further over time because he was a philosopher with a passion for wildflowers as much as a landscape architect. Waltham Place was certainly cutting edge at the start of the new millenium.

Knepp Castle, in the same episode, is very recent – just a few years old, in fact. I haven’t been there but it appears to be the new cutting edge, arousing strong opinions. I have heard it praised to the sky but also savaged as a travesty of a traditional, walled garden.

Walled gardens are not uncommon in Britain. Often encompassing areas that are measured in acres and a lasting monument to brickies of old, they were originally sheltered kitchen gardens, orchards and picking gardens so productive and utilitarian. These days, they are widely repurposed as ornamental gardens. It is quite a leap to change them from being a productive garden in times past to being purely ornamental as at Scampston Hall. Is it such a big leap to then heavily modify the contour and soil to make a naturalistic garden?

I was going to say that, to me, Knepp Castle looks like having its roots in Beth Chatto’s dry garden from the 1960s with strong elements of James Hitchmough’s Missouri meadow at Wisley from the mid 2000s, meeting Tom Stuart-Smith’s expansive perennial terraces, some modern European gardens and generous lashings of what Keith Wiley has created at Wildside – but all combined in a project started in 2020. I looked up their website and indeed the designers involved included Stuart-Smith and Hitchmough as well as Jekka McVicar and Mick Crawley whom I had not heard of but is apparently an emeritus professor of plant ecology at Imperial College in London. That is quite the team.

I am with Monty Don. I hesitate use the words rewilding, or even restorative gardening at Knepp Castle, but I love the naturalistic look and the underpinning principles of gardening in cooperation with Nature, not by iron-fisted, human control. But you have to intervene all the time, as the owner said, or it will just be taken over by weeds. My reservations – and, it seems, Monty’s – are about semantics not principles or indeed the end result which is a lovely example of modern naturalism in gardening, rich in plant interest.

To me, rewilding and restoration are more akin to what we know in this country as ‘riparian planting’***. Or maybe planting an area in eco-sourced natives or shutting up an existing area of native plants and then assiduously weeding out invading plants of exotic origin. That is not gardening.

What is being referred to as rewilding or restorative gardening in Britain is what we describe as naturalistic gardening, sometimes veering into wild gardening. Same principles, different words.

It seems to me that the controversial aspect of Knepp Castle lies mostly in the repurposing of a walled garden to carry out this experiment in naturalism. I have only seen it in episode 4 of Monty Don’s British gardens but I have watched that segment three times. I much preferred it to the walled garden (I think in episode 3) which had been planted out in wide rows of perennials as a nod to its more traditional food producing days. That one had all the romance and panache of production nursery stock beds in our eyes (retired nursery people here) with none of the skills and delights of plant combinations, let alone any actual merit in design.

I would put Knepp Castle on my visiting list, were I planning another trip to Britain, even though I struggle with the idea of thinking like a beaver or a wild boar when it comes to garden maintenance.

***Riparian planting is being strongly promoted by our regional councils, mandatory in some situations. It is fencing off and planting the banks of waterways, generally in native plants, with the aim of preventing farmland runoff contaminating rivers and streams. In quaint rural parlance, I understand the measure of a waterway that should – or must – be fenced and planted is that it be ‘wider than a stride and deeper than a Redband’. Redband is the brand of gumboots most often worn in farming communities. That is probably what most people in this country would see as rewilding.