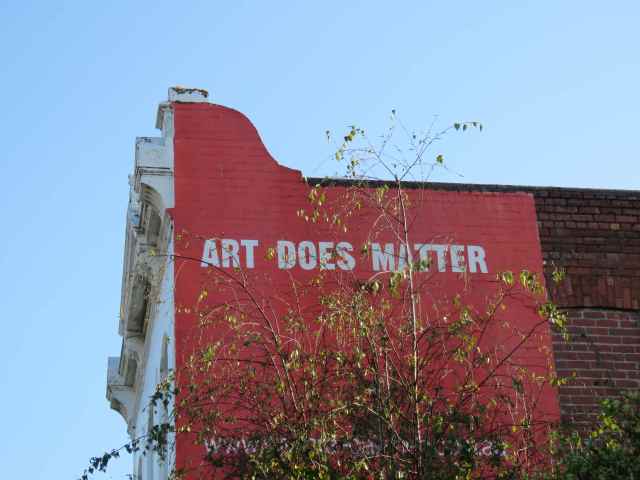

Lead photo: Magnolia ‘Ruby Tuesday’™

It can take a long time for a new plant from Mark’s breeding programme to reach the point of sale on the market. We have long since moved on to looking at more recent plants but it is a thrill when the time comes to seeing the plants finally released commercially into the wider world.

It was different when we had the nursery and we would release new plants onto the domestic market. There could be a quick turnaround on those. Nowadays, we focus internationally and that is a very different ball game. It has become increasingly difficult and eyewateringly expensive to get new plants into other countries, through quarantine, trialled and then built up commercially for release. Aside from controlling the initial selection and supply of plant material for propagation, everything is done by our Australian-based agents these days – Anthony Tesselaar Plants – and for this we are truly grateful because it is a plant mission.

This year heralds the start of a new round of plant releases – three new deciduous magnolias and the next evergreen in the Fairy Magnolia® series – but not simultaneously.

First up, there will be a limited release this year in Aotearoa New Zealand of the three deciduous magnolias, 2026 for Australia and then or soon after for Europe. Don’t even ask about USA – a work in progress there but likely to be longer.

Magnolia ‘Ruby Tuesday’™ will the last of the Jury red magnolias to be named and released. It all started with Felix’s ‘Vulcan’, a breakthrough that has well and truly stood the test of time. Mark followed up with ‘Black Tulip’, ‘Burgundy Star’ and ‘Felix Jury’ – the latter varying in colour from deep red to rosy pink, depending on growing conditions. ‘Black Tulip’ and ‘Felix Jury’ in particular have become influential in international magnolia breeding. I see many photos of plants that have one or other of them in their parentage. I may be biased but I don’t see many that are an improvement on their parent.

It seems fitting that we end the Jury reds with Magnolia ‘Ruby Tuesday’™ because we regard it as a significant upgrade on ‘Vulcan’. It has all the desirable characteristics of ‘Vulcan’ – rich colour, smaller tree, flowering from a young age and very floriferous. But better. It loses the less desirable aspects of ‘Vulcan’. It blooms a little later in the season which is better for colder climates; it has a long flowering season and the later season flowers are as good as the earlier ones (which is not always the case with magnolias). But best of all, it has lost the purple undertones that were the main problem with ‘Vulcan’ – especially as the season progressed when the brilliant early blooms could give way to smaller flowers which tended to be rather murky and paler in colour. ‘Ruby Tuesday’ stays the same clear red from start to finish. We describe it as ‘garden friendly’ which means it is a suitable size for smaller, domestic gardens – still a tree but a smaller specimen. We are very proud of it.

Second up is Magnolia ‘Ab Fab’™, the only white magnolia Mark has named. His initial code name has stuck – it is named primarily for me with a nod to Jennifer Saunders and Joanna Lumley and I feel in excellent company there. It has a huge white bloom with just a touch of pink at the petal base and we do like big flowers on our magnolias here. So, in flower size, it sits alongside Felix’s ‘Atlas’ and Mark’s ‘Felix Jury’. I was amused to be sent a photograph of it flowering in a European nursery – in Germany, from memory – of a bare stick about 1.5 metres high adorned with several excessively large white blooms. It looked impressive but is even more impressive on the original plant. It is a larger growing tree and we worried for a while that it may be too large but growth rates and size are heavily determined by climate and most magnolias around the world are grown in harder conditions than we ever get here so it is unlikely to reach the same stature that we see.

We have really struggled with naming the third one. In the end, I crowd-sourced a name on the social media platform, Bluesky. Out of hundreds of suggestions, we came up with a short list of of nine good names and I think we have settled on Magnolia ‘Dawn Light’™. Our problem came with trying to nail down the colour. Depending on light conditions, it is somewhere between rich pink and purple. I lined up petals alongside Magnolia campbellii var mollicomata ‘Lanarth’, one of the purplest of the species and the petals of the hybrid were darker but it doesn’t always look that way on the tree. It is not blue enough to be able to say it is purple, lilac or lavender, not brown enough to be puce, but possibly too many blue hues to be rich pink. Hence ‘Dawn Light’™. Whatever the colour, it is lovely and has been a consistent performer in a prominent position here year on year. It is another taller, upright grower – rather than spreading – but is not likely to be as tall in different climates.

These three cultivars have been under our watchful eye for years and we are confident on their merits. Magnolias are a long term plant. You don’t want to be casting a plant out after 5 or 10 years because something better comes along. We think these three will stand the test of time.

Australia is as difficult to get through border control as Aotearoa NZ is so it has taken a long time for Mark’s Magnolia ‘Honey Tulip’ to be released there, even though it has been sold in this country, in Europe and the UK for some time. But at last it is ready for release in Australia this year.

However, Australia gets the first chance at Fairy Magnolia ‘Petite Peach’™ which will be released this year (2026 in NZ and 2026/27 in Europe). Sharp-eyed garden visitors may have spotted the two clipped, smaller pompoms at our gate. ‘Petite Peach’ has been well trialled down the years here. It is much more compact than the three Fairy Magnolias® already released, with smaller foliage and a mass of smaller blooms in peach shades. It is what we would describe as a ‘good garden plant’ – reliable, consistent, extremely healthy, able to fit into gardens of any size and pretty, rather than spectacular.

Meantime, we are into the final year or maybe two of assessing what is likely to be the last tranche of Jury hybrids from this generation of the Jury family. It is likely there will be a couple more deciduous magnolias but yellow this time, and maybe another three or four different colours in the ‘Fairy Magnolia’® series. But don’t hold your breath. These will be years off being released internationally. Plant breeding with the magnolia genus is definitely a long term project.

Postscript: For the magnolia aficionados who are going to ask about the breeding, these are largely from crossing hybrids but if you take it back to the originating species it works out to the following:

Magnolia ‘Ruby Tuesday’™ M.soulangeana x ‘Lennei’ – so some liliiflora – x {M.campbellii mollicomata ‘Lanarth’ x M. sargentiana robusta} x {M. liliiflora hybrid x ‘Lanarth’}. Which translates to 3/8 ‘Lanarth’, around 3/8 different forms of liliiflora with some sargentiana robusta and a few unknown genes to make the full quota.

Magnolia ‘Ab Fab’™ (M. soulangeana x ‘Lennei’ – so some liliiflora – x {M.campbellii mollicomata ‘Lanarth’ x M. sargentiana robusta}) x M. x ‘Lennei alba’ (liliiflora genes again with some denudata) x {M.campbellii var mollicomata ‘Lanarth’ x M. sargentiana robusta}. Which makes the dominant genes liliiflora followed by ‘Lanarth’ and sargentiana robusta.

Magnolia ‘Dawn Light’™ (M. soulangeana X ‘Lennei’ – so some liliiflora – x {M.campbellii var mollicomata ‘Lanarth’ x M.sargentiana robusta} x ‘Lanarth. So the dominant genes in this one are ‘Lanarth’ with lesser amounts of M. sargentiana robusta and M. liliiflora.

In layperson’s terms, Mark has continued using his father’s lucky break with the hybrid seedling he was sent which he named Magnolia ‘Mark Jury’ (back in the 1950s), crossing with the downstream Jury hybrids both he and Felix created, plus ‘Lanarth’.