Written for and first published in the International Magnolia Society journal. In the time since writing the text and publication, we are now able to release details of the three new deciduous magnolia hybrids being released internationally.

The Jury magnolia reputation rests on just twelve deciduous magnolias so far. Soon there will be fifteen and it may end up at seventeen in total. Despite originating on a farm in far-flung New Zealand, some of those plants have had a significant impact in the international magnolia world.

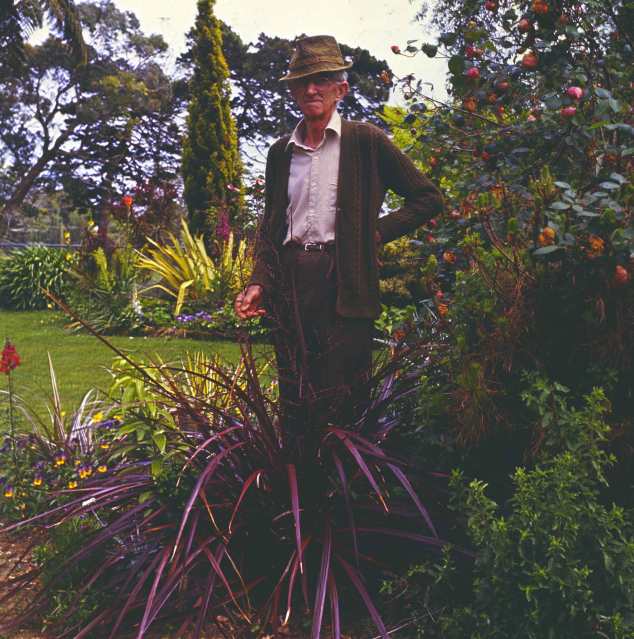

Felix Jury was a farmer who decided he would rather garden. He handed over the family farm to his second son as soon as he could and devoted his time and energy to building a large garden. He started by buying plants, importing new material from around the world. It was the failure of many of these to thrive in our warm temperate conditions that started him on the hybridising path. He was a self-taught amateur; like many of his contemporaries of the day, he became proficient at raising seed, striking cuttings, budding and grafting across a wide range of genus but it was always on a small scale, hobby basis. For an amateur, some of his plants have stood the test of time across the world. Phormium ‘Yellow Wave’ is still being produced internationally in surprisingly large numbers and Camellias ‘Dreamboat’ and ‘Waterlily’ have remained household names in the camellia world. He never received a cent in payment for any of these plants. Over time, it is his magnolias that have firmly cemented his name in international gardening.

Mark Jury was Felix’s youngest son. By the time Mark and I returned to the family property in 1980 with Mark planning to set up a plant nursery, his father had scaled down his adventures with plants and quietly retired to the garden. It was a privilege for both father and son to have seventeen years working closely together in remarkable harmony. Felix was able to transfer all his knowledge and experience to Mark who was keen to continue the garden development and to take the plant breeding to the next level. Unlike his father, Mark needed to generate an income. Also self-taught, Mark started the nursery, literally building up from one wheelbarrow to a successful boutique business doing mail-order, wholesale and on-site retail.

Felix didn’t raise large numbers of magnolias from his controlled crosses. They would probably number no more than fifty and over a few years only in the 1960s. Of these, eight ended up being named and released commercially. Technically, there were nine but we will return to the irritating matter of the ninth later. He would have named more but Mark vetoed that. From an early stage, Mark took the view that fewer and more stringent selections were better than more when it comes to a genus with the potential to be long-term trees in the landscape.

Of those eight, Mark has felt that probably only six should have been named. He singles out sister seedlings ‘Milky Way’ and ‘Athene’ as two that could have been narrowed down to one. For a long time, he said the same thing of ‘Iolanthe’ and ‘Atlas’ but has had to change his tune. While we regard ‘Iolanthe’ as a flagship magnolia, arguably one of the best two Felix bred in New Zealand conditions, it has never performed as well overseas and is certainly not rated as highly elsewhere. ‘Atlas’ has a larger bloom and is a prettier pink but its flowering season is short – by our standards – and we don’t often see it in its full glory because the petals are too soft and get badly weather-marked. But ‘Atlas’ appears to be hardier in overseas climates and a better performer elsewhere than it is here.

In those days, the range of magnolias available commercially was small. Felix’s initial goal was to see if he could create hybrids that would flower on young plants and stay a garden-friendly size. It was generally accepted that when a magnolia was planted, it was realistic to expect a delay of between about seven and fifteen years to get the first blooms. He also liked the cup and saucer flower form and he wanted more colour. Of his named hybrids, six of the eight had a chance hybrid in their parentage. It was the cross he received from Hillier’s Nursery as a seedling of M. campbellii var mollicomata ‘Lanarth’. Mark has always referred to it as his father’s secret weapon. When it flowered, it was clear it was not ‘Lanarth’ but a hybrid, presumed to be with M. sargentiana robusta. He duly named it for his favourite son so it is known as Magnolia ‘Mark Jury’.

Felix’s two greatest achievements were in creating large-flowered hybrids that bloomed on young plants and in introducing the breakthrough to red shades with his cultivar ‘Vulcan’.

Possibly under-appreciated are the additional factors of heavy textured petals, solid flower form and the setting of flower buds down the stems so blooms open in sequence, rather than just tip buds that all open at once for a mass display that may only last a fortnight. Our springtime is characterised by unsettled weather; Mark refers to the magnolia storms. One overnight storm can destroy the display of softer booms like M. sprengeri var. ‘Diva’ or wipe out the tip bud display of ‘Sweetheart’ (a ‘Caerhays Belle’ seedling).

The performance of ‘Vulcan’ around the world has been well documented and ranges from brilliant to undeniably disappointing.

I will say that ‘Vulcan’ was the only plant we have ever put on the market which we could track its flowering by the phone calls we received year on year. Being a long, thin country in the southern latitudes, magnolias open first in the warmer north and then in sequence heading down the country. The phone would start ringing in early June from the north and continue through August from more southern areas. That is a stand-out plant.

Whatever its flaws, ‘Vulcan’ opened the door to the plethora of red hybrids now available internationally and it remains a key foundation plant in the development of new hybrids.

Mark started hybridising magnolias in the 1980s, picking up where his father had left off and using the same genetic base. He has raised many more controlled crosses than his father ever did. We have never counted how many but it will be well into the thousands. Of those, only four have been named and released and there is another tranche of three which are being built up for release internationally. That makes seven Mark Jury magnolias and all are distinctly different.

Ill health has cut short Mark’s breeding programme and we are now assessing the final batches of his breeding efforts. He has already decided that he has done as much as he can with the reds so he has ruled out the next generations of those and we are now looking at his yellows. We are hopeful that we will get maybe two final selections so he may end up with nine named magnolias in total.

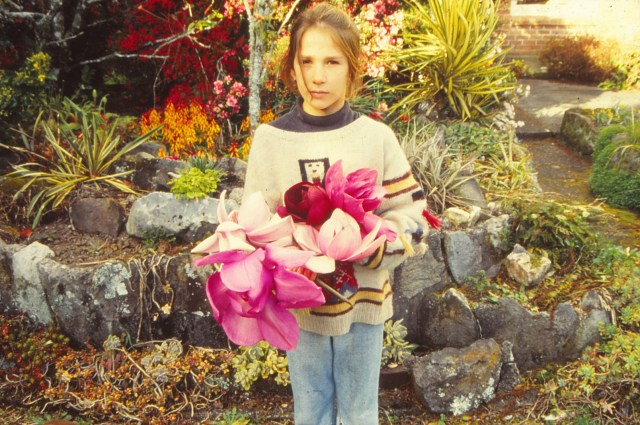

He has always been particularly proud of the cultivar he named for his father, Magnolia ‘Felix Jury’. He reached the goal Felix had set – a tree that will not get excessively large but with very large, colourful blooms from an early age. It has always delighted us that Felix was still alive to see it bloom. In our climate, the colour can vary from rich pink through to deep red, at its best. Over the years, we have learned that the colour in magnolias can bleach out, particularly in colder climates, and we get exceptionally rich colour in New Zealand. Presumably this is related to the very clear light that we have, along with the soils and mild climate (never very hot and never particularly cold). ‘Felix Jury’ keeps its size and form in different climates and even when the colour is lighter in shade, it is an acceptable pink, albeit not the stronger shades we see here.

Both Mark’s ‘Black Tulip’ and ‘Felix Jury’ are showing up in the breeding of countless cultivars across the magnolia world and are clearly having long-term influence. ‘Black Tulip’ sets seed readily and it seems every man, woman and their dog have raised seedlings, judging by the photos we have seen. None appear to be an improvement on the parent to our eyes and not many have taken it in a different direction. But its impact on the development of new hybrids is clear to see. Mark has raised hundreds of his own ‘Black Tulip’ hybrids so we see many, many lookalikes but few stand-outs.

We have high hopes of the last red he has selected which is one of the three new ones to be released. He bypassed ‘Black Tulip’ and went back to his father’s ‘Vulcan’ as one of the parents. We don’t rush selections based on flower alone; this one goes back 20 years but its shade of red stood out from the start and the original plant has never had an off-season. It has lost the muddy purple undertones of ‘Vulcan’ and keeps its rich shade of red right through the exceptionally long flowering season. It starts a little later than ‘Vulcan’ so is less vulnerable to late frosts and the late season blooms are as good as the first ones. We describe it as a ‘Vulcan’ upgrade. It has kept the best features but eliminated the undesirable characteristics. Only time will tell if this is true in other climates but keep an eye out for this ruby red selection in the coming years.

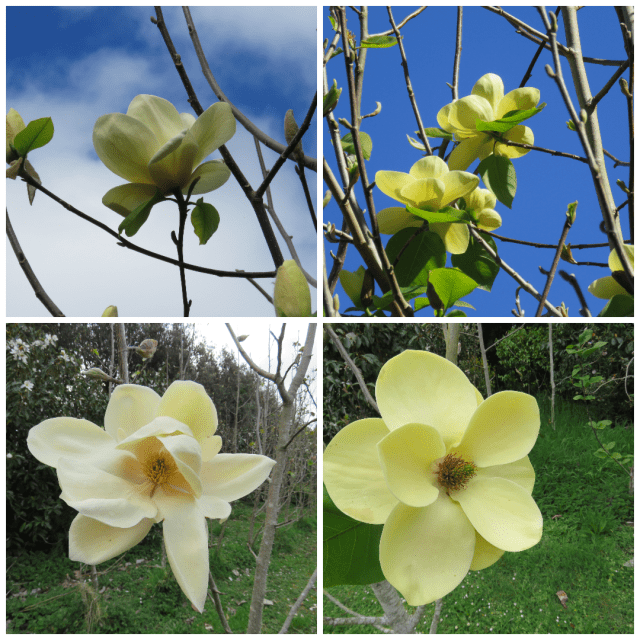

Mark turned his attention to the yellows. The magnolia world is awash with yellow hybrids, so many that it is hard to pick out the ones that are superior. Mark’s dream was of a big, pure yellow flower in the cup and saucer form of M.campbellii but on a tree that opens its flowers before its foliage appears, and in a garden-friendly size. A yellow ‘Iolanthe’ or ‘Felix Jury’, so to speak.

His ‘Honey Tulip’ was a step on the way. It was a break away from the pointed buds, narrow petals and small flowers that come from the dominant M.acuminata parentage. It isn’t the butter yellow he wanted but it met the brief of solid flower structure and thick texture, flowered before leaf-break and stayed small enough for most gardens. Importantly, the colour does not fade out as the season progresses.

The next generations have taken it further. He has the strong, clear yellow he wanted, the large flower size, the flower form, the slightly earlier blooming season to beat leaf-break and the garden friendly habit of growth. He just doesn’t have them all on the same plant.

The goal of a big, pure yellow, cup and saucer magnolia is achievable but Mark has run out of time and energy. It will take another generation of plant breeder to reach it. That said, there are probably a couple of good yellows that are significant steps along the way that we should get out of the last batch of seedlings. One, in particular, is a very pretty lemon-yellow (so not the strong colour he wanted but still yellow) with the desired flower size and form and it is blooming from an early age although the flowers coincide with leaf-break. It is hard to reach perfection.

There are a few striking sunset mixes of strong colour on goblet shaped blooms but none of them look good enough to select. Plant selection is always made on a variety of criteria but Mark’s personal preference for solid colour is strong. Every magnolia he has named is one colour inside and out because that is what he likes. I had to twist his arm to even look at the sunset mixes; he does not think pink and yellow is a pleasing combination. He is also dismissive of what he calls ‘novelty blooms’. I marked one seedling that had distinctive, caramel-coloured blooms. Viewed close-up, they are interesting but I had to concede he was right. On the tree, they will just look like they have been hit by frost.

Always, we are selecting for plants that will look good over time in the landscape. Looking interesting as a cut flower in a vase is not enough, given the magnolia is a landscape tree with long term potential.

I mentioned the irritating ninth Felix Jury hybrid at the start. It is Magnolia ‘Eleanor May’ and I wouldn’t even reference it except I saw a photo lauding its merits in the UK this year. I don’t have a photo of it in my files which indicates the low esteem we hold it in. While it is a seedling from Felix’s breeding programme, we don’t claim it as a Jury hybrid. It is a full sister to ‘Iolanthe’ and a rejected seedling. Felix provided material of it to the nursery Duncan and Davies to use as a good root stock. From there, the nursery sent out a few failed grafts of ‘Iolanthe’ to garden centres by mistake. One plant was purchased by a customer who was observant enough to pick the difference when it flowered. He then took it upon himself to name it for his wife which may have been legal but was certainly lacking in courtesy. As far as we are concerned, it is inferior to ‘Iolanthe’, had already been rejected in selection and was an escapee by mistake. Besides, when we question releasing two of the same cross – ‘Iolanthe’ and ‘Atlas’ – why would we want to claim a third of the same cross? We have a property filled with sister seedlings which we would hate to see unleashed onto an over-crowded magnolia market.

Mark’s more recent work with hardier members of the michelia group is another story. The first three selections are on the international market under the Fairy Magnolia® branding. They are in white, cream and soft pink and the next two on the way are in shades of peach and blackberry ripple. We are now onto the final round of selections which are into the bicolours and purple.

Again, he has come up short on a strong yellow that is good enough to select and, regretfully, the really pretty apricot ones have not made the grade. But we know that those colours are within reach without sacrificing hardiness. Mark wryly describes his work on michelias as ‘RFI’. That is Room for Improvement. It will take another breeder to get there but there is plenty of promise and scope to take them further.

Felix Jury magnolias

Apollo (probably liliiflora nigra hybrid x campbellii var mollicomata ‘Lanarth’)

Athene (‘Lennei Alba’ x ‘Mark Jury’)

Atlas (‘Lennei’ x ‘Mark Jury’)

Iolanthe (‘Lennei’ x ‘Mark Jury’)

Lotus (‘Lennei Alba’ x ‘Mark Jury’)

Milky Way (‘Lennei Alba’ x ‘Mark Jury’)

Serene (liliflora x ‘Mark Jury’)

Vulcan (liliiflora hybrid x ‘Lanarth’)

Mark Jury magnolias

Black Tulip (‘Vulcan’ x)

Burgundy Star™ (liliiflora nigra x ‘Vulcan’)

Felix Jury (‘Atlas’ x ‘Vulcan’)

Honey Tulip (‘Yellow Bird’ x ‘Iolanthe’)

Plus Ruby Tuesday, Dawn Light and Ab Fab

Fairy Magnolia® Blush (M. laevifolia x foggii hybrid)

Fairy Magnolia® Cream (M. laevifolia x foggii hybrid)

Fairy Magnolia® White (M. laevifolia x doltsopa)

Fairy Magnolia® Lime (on very limited release in Europe only)

Plus Fairy Magnolia® Petite Peach